Immunotherapy drugs known as checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized cancer treatment: many patients with malignancies that until recently would have been considered untreatable are experiencing long-term remissions. But the majority of patients don’t respond to these drugs, and they work far better in some cancers than others, for reasons that have befuddled scientists. Now, UC San Francisco researchers have identified a surprising phenomenon that may explain why many cancers don’t respond to these drugs, and hints at new strategies to unleash the immune system against disease.

“In the best-case scenarios, like melanoma, only 20 to 30 percent of patients respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors, while in other cases, like prostate cancer, there is only a single-digit response rate,” said Robert Blelloch, MD, PhD, professor of urology at UCSF and senior author of the new study, published April 4 in Cell. “That means a majority of patients are not responding. We wanted to know why.”

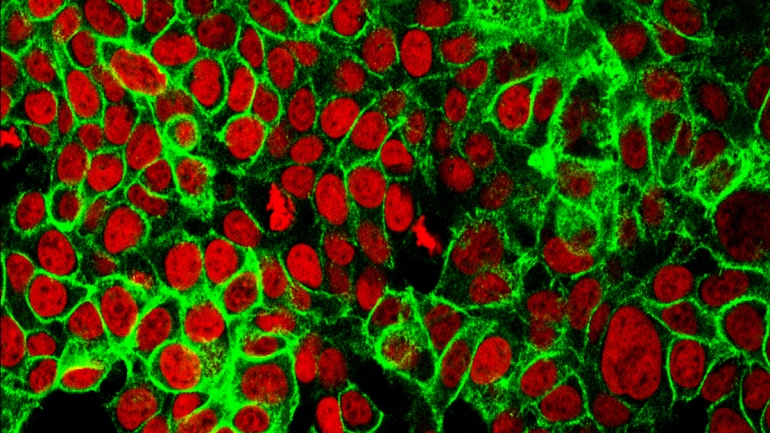

In malignant tissue, a protein called PD-L1 functions as an “invisibility cloak”: by displaying PD-L1 on their surfaces, cancer cells protect themselves from attacks by the immune system. Some of the most successful immunotherapies work by interfering with PD-L1 or with its receptor, PD-1, which resides on immune cells. When the interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1 is blocked, tumors lose their ability to hide from the immune system and become vulnerable to anti-cancer immune attacks.

One reason that some tumors may be resistant to these treatments is that they do not produce PD-L1, meaning that there is nowhere for existing checkpoint inhibitors to act — that is, they may avoid the immune system using other checkpoint proteins yet to be discovered. Scientists have previously shown the PD-L1 protein to be present at low levels, or completely absent, in tumor cells of prostate cancer patients, potentially explaining their resistance to the therapy.

Read full article via UCSF.edu